Expatriate Life in Saudi Arabia: Khobar Massacre 2004

Just before we left Saudi Arabia in December 2008, I wrote this email since I had never before documented the Khobar massacre which occurred during our time there, and in which we were all on lock-down over an extended period of time.

|

| Desert camping with boys 2004 |

Saudi Aramco, Dhahran, December 2008:

It’s been years, literally, since I wrote about our life here in Saudi as opposed to our lives with kids. Today, strangely enough, I came across the beginning of an email I started exactly three years ago to the very day, touching upon what life is like here on Aramco, since it differs greatly from general expatriate life in Saudi. However, I never finished what I begun on the 7th August 2005 and three years later I still haven’t finished it. (And it took me a further six weeks of rumination, internal debate and external research, before I was ready to send this one off).

But somewhere along the line I felt it necessary to sketch in the background, and not just focus on the foreground. There’s always been this complaint about Jane Austen, that she writes of the soldiers but not of the war – directly. Not that I’ll get into the merits or demerits of such arguments. But Austen could assume a certain working knowledge within her readers of the Napoleonic Wars and Peninsular Campaign. The longer we live here the less it feels like we are part of a common war, though you’d think we’d all have common enough cause.

Recently, as we’ve been travelling, I am finding, more and more, that there is this perception of where and how we live that is out-of-kilter with how we consider ourselves to be living. Which is not to say we may not have the larger picture wrong. But a word that kept coming up, particularly in conversations with South Africans was that of us being “safe” here. Well, we sure hope so, and life is, after all, always contingent, but frankly, the odds are fairly incalculable, and like all such odds, only work backwards anyway. So we do what everyone does, carry on living, worry intermittently about the future, and hope for the best.

To begin at the beginning: Fem arrived to take up formal, full-time employment (i.e., we were no longer working on contract) on Saudi Aramco, Dhahran, on the 11th September 2003 (which means he has just completed a five year stint on Aramco), and I followed in late October, heavily pregnant with Conall and with a 13-month old Faran. I don’t know if we’d have made the move then if Fem hadn’t first gone to Saudi in 2000, before any of us knew of a strange little organisation called Al Qaeda.

Recently, as we’ve been travelling, I am finding, more and more, that there is this perception of where and how we live that is out-of-kilter with how we consider ourselves to be living. Which is not to say we may not have the larger picture wrong. But a word that kept coming up, particularly in conversations with South Africans was that of us being “safe” here. Well, we sure hope so, and life is, after all, always contingent, but frankly, the odds are fairly incalculable, and like all such odds, only work backwards anyway. So we do what everyone does, carry on living, worry intermittently about the future, and hope for the best.

To begin at the beginning: Fem arrived to take up formal, full-time employment (i.e., we were no longer working on contract) on Saudi Aramco, Dhahran, on the 11th September 2003 (which means he has just completed a five year stint on Aramco), and I followed in late October, heavily pregnant with Conall and with a 13-month old Faran. I don’t know if we’d have made the move then if Fem hadn’t first gone to Saudi in 2000, before any of us knew of a strange little organisation called Al Qaeda.

But here we were, relocating again at a time when expatriates were being bombed in their compounds, particularly in the Riyadh area, and every time I started to compose something about what it was like here, yet another terror incident would occur and I would close down the email for a while, full of dread that I’d wax lyrical about our life of privilege here only to watch the House of Sauds proceed to fall flat and reverberate all across the Saudi desert.

|

| Conall in desert, 2004 |

It all culminated in the horrific Oasis incident in Khobar on the 29 May 2004 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2004_Khobar_massacre) which was just way, way too close for comfort - not that far from Aramco and literally just down the street from where we had lived for almost two years at Al Yamamas. I always walked past the Oasis compound on my way for my prenatal check-ups when pregnant with Faran. In fact, so large is the compound that it comprised a good part of the five kilometre walk. The incident was followed by weeks of tracking the group down and then months and months that stretched into years of reports of Saudi security forces being in deadly gun battles with holed-up gangs of desperate Al Qaeda suspects.

The British Ambassador then said that we were probably facing living with low-level, chronic terrorism in the country, and that certainly continues to this day; in 2006 there was a thwarted attempt on the Aramco facility about an hour’s drive away – the car bomb was detonated and a shoot-out occurred just after the first set of gates. We always wanted to visit Mada’in Saleh, considered a sister city to Petra, but currently it may not be possible after the killing of tourists there in February 2007. A friend of ours went camping in the desert near Riyadh not long after that incident and he and his entire party were surrounded by security forces and they were cordially escorted out from the area – they even phoned his boss at 2am in the morning to report when the party had gone ‘missing’ (they had merely camped for the night and lost track of them). They never again were out of sight of armoured vehicles, and he reports that, having endured the embarrassment of an armed escort through Riyadh, it remains low on his wish list.

Later on in the year the Saudi government reported rounding up “208 people in the country suspected of having ties to Al Qaeda and who had been planning attacks on oil facilities in the Eastern Province and killings of clerics and security forces” (NY Times November 29 2007). The total to date for this year is 701, and the American, Australian and British Embassies have recently issued travel warnings based on the “high threat” of militants plotting new attacks. “The Australian government issued a warning yesterday asking its citizens to consider whether they need to travel to the Kingdom ‘at this time due to the very high threat of terrorist attack’” (Arab News, 26 August 2008). On their web-site travel advisory, the Australian government reports, “Statements by international terrorist groups continue to call for attacks against Westerners on the Arabian Peninsula. These include references to residential compounds, military, oil, transport and aviation interests.” (http://www.smartraveller.gov.au/zw-cgi/view/advice/saudi_arabia). I don’t think it takes a genius to ascertain that a certain level of vulnerability can be felt by a blonde-haired (i.e., clearly foreign) female living in a residential compound which is also the headquarters of the oil company of Saudi Arabia, otherwise known as the “King’s company” since it is from Saudi Aramco that the Saudi Royal’s wealth is secured.

Later on in the year the Saudi government reported rounding up “208 people in the country suspected of having ties to Al Qaeda and who had been planning attacks on oil facilities in the Eastern Province and killings of clerics and security forces” (NY Times November 29 2007). The total to date for this year is 701, and the American, Australian and British Embassies have recently issued travel warnings based on the “high threat” of militants plotting new attacks. “The Australian government issued a warning yesterday asking its citizens to consider whether they need to travel to the Kingdom ‘at this time due to the very high threat of terrorist attack’” (Arab News, 26 August 2008). On their web-site travel advisory, the Australian government reports, “Statements by international terrorist groups continue to call for attacks against Westerners on the Arabian Peninsula. These include references to residential compounds, military, oil, transport and aviation interests.” (http://www.smartraveller.gov.au/zw-cgi/view/advice/saudi_arabia). I don’t think it takes a genius to ascertain that a certain level of vulnerability can be felt by a blonde-haired (i.e., clearly foreign) female living in a residential compound which is also the headquarters of the oil company of Saudi Arabia, otherwise known as the “King’s company” since it is from Saudi Aramco that the Saudi Royal’s wealth is secured.

|

| 8 months pregnant with a 13 month old, December 2003 |

The Khobar massacre in 2004 was followed by weeks of sheer terror when no-one was at all sure about what was going on and it felt as if the country was on a knife-edge. Apart from my nearest and dearest, only a few people seemed to know about the situation – or at least in terms of writing or calling (thank you very much indeed to those who did). Certainly the South African print press, as opposed to the American, hardly picked up the story at all, and many people to this day simply conflate where we are living with Dubai, which is easily enough done since so many more South Africans are currently working there than are here in Saudi. However, Saudi Arabia and Dubai are about as similar as Alexander Township is to Sandton. While they are geographically proximate in most other respects the differences are glaring. Two words: Fundamentalist. Cosmopolitan.

Then again, it’s not as if we were squealing merrily about it, it was one of those times when it’s easier to grit your teeth and endure than talk about it. We all have our own ways of coping with situations, I find for myself that talking to all and sundry about a situation over which I have no control and to which I have absolutely no answers often just makes things less endurable for me, for as the angel lady puts it, what you focus upon grows. Females are apparently particularly prone to “co-rumination” as the balky term is applied, but I am not found in their number. Do not ask me to dwell on something in the expectation of clarity and reassurance, I’ll not be found huddled in the middle, towards the campfire, bonding, worrying about whether to stay or go, but ranging the perimeter, seeking a way forward or out. Besides, I felt there were enough people focusing on the horror! the horror! of it all, I didn’t feel like adding my small hill of misery to that growing mountain of despair.

Hence, a few days after the massacre Fem and I were to be found, not part of a group convened by our American friends inside Aramco to “discuss the situation”, but outside Aramco, having dinner with Hadeel and Ammar, just down the street from where it all happened. I am pleased to be able to report that we all managed to laugh a lot that night. But apart from those few shining moments, the mass hysteria was very draining. At least I’d had the experience of people equally terrified in the run-up to the, in-the-end peaceful elections of 1994 in South Africa and so was not wholly surprised when the age-old urban legends that were rife in South Africa then re-surfaced with new Middle Eastern twists, the same old stories re-treaded for new audiences. Interestingly enough, the people telling and re-telling them or listening to them stayed on in Saudi Arabia, they appeared to need to feel the frisson of terror run through them, much as in a deserted house you listen to ghost stories to get the adrenaline going, whereas the others spent no time telling or listening to stories, but spent it packing instead. It was however a particularly peculiar baptism of fire into life on Saudi Aramco, which inevitably changed dramatically as a direct result of it all. (It was also, incidentally, the reason I became involved in the Women’s Group, there were too few people in the Kingdom left to run it and hence it was threatened with closure and that was when my involvement began, despite the fact that I had a new born and a 15-month old baby on my hands at the time).

|

| Bethany discovering sand, 2007 |

But we really did feel absolutely and completely at sea amidst a swirl of rumour and conjecture and, having just begun to settle at Aramco, we found ourselves surrounded by a mass of completely hysterical people who were leaving. Entire swathes of families packed up and left without so much as even shaking the dust off their feet (to this day we have no official account of the numbers who fled, but at least 128 families left Aramco alone within a two month period, many who had been here for up to 20 years, and, of all the compounds, the Aramcons were most likely to stay based on length of time in the Kingdom, massive privileges and excessive security surrounding them). Some families relocated to Bahrain while the husband commuted to Saudi Arabia, and within those others who stayed on, the wives of many families (with the company’s full and explicit permission) simply lived outside the country near their grown children for entire years thereafter. In fact, the company is still battling to strip away the privileges it granted us then, a full five years later (these included hugely extended leave for wives – as it is, I only have to be in the country 6 months of any given year before Fem loses “family” status. We were also granted double shipping allowances, so you could ship your most valuable good out of the country. Of course, in one of life’s little ironies, my friend, Ilaria, who shipped her valuables to Italy at this time, has just discovered they were stolen from the basement where her brother stored them.)

At the time of the Khobar massacre, I had a 19 month old and a 4 month old, and of course when you have very tiny babies you do feel more fragile generally since they are so precious and so small, and your body is full of hormones coursing through your body urging you to protect your babies and Fem was just settling into his job here and it was our fifth international relocation in three years which had set us back financially enough that leaving wasn’t really a sane option if things were endurable, since contractually we’d be obliged to fund such a move entirely ourselves and he’d already been out of work for three months before our arrival since he ended up in a position where resigning became the only ethical option. He had signed a contract of employment with one section of Saudi Aramco, which took a further three months to process the visa, but during this time he was offered a year’s contract through his South African company to work at another part of Saudi Aramco. Hence he felt he was forced by circumstance to declare his intentions lest he forever spoil relations with either company. And emotionally I was running on empty, empty, empty.

|

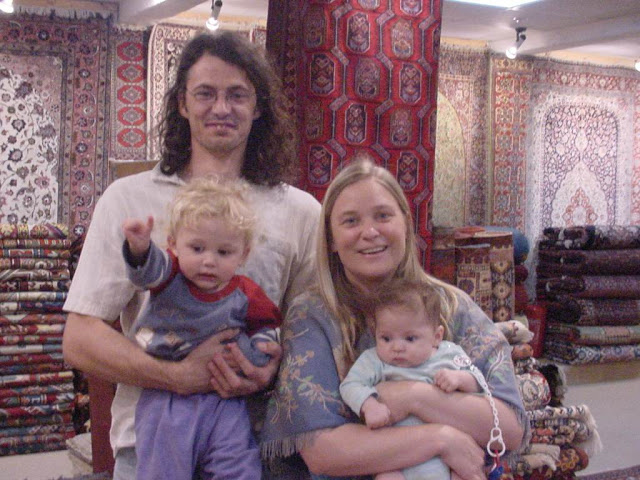

| Eastern Carpet House, Amjad Alis's fantastic shop in Al Khobar, 22004 |

What I did learn from the experience was that you can’t rely entirely upon the world media for analysis. The only, and I repeat, the only newspaper that produced articles freely available on the internet and which you could read and analyse and use to understand the security forces versus terrorists situation and which did in fact therefore prove to be accurate after-the-fact was the New York Times. We know they get other situations wrong enough (WMD for one, with much accompanying self-flagellation), but at least they can give an analyst some space in which to develop an article, and, based as it was on sources such as Jane’s Defence Weekly and in-depth interviews and understandings of what it takes to keep a terror cell going (about 100 otherwise ordinary people per cell who work on the outside to keep it going, so general feelings of good-will towards the terrorists within a country not at war is required to keep cells active), the analyses given were fact-based, and as such, as useful at it can get. Apart from those few, the rest were mostly hysterical, a few Reuters facts regurgitated ad infinitum and interspersed with conjecture. It appeared then that selling newspapers was of paramount importance and getting it right entirely secondary. A common enough complaint against newspapers since time immemorial; it’s just when you are otherwise working in the dark, blinded by not knowing or understanding the forces of a different religion, other conventions and another language, you really do long for something a bit more substantial.

I also discovered, from my friendship with Hadeel, who was avidly watching the Arab news channels on TV, how little able the Western world is to decode, never mind sympathise with, a world falling under Islam, given their total reliance on secular sources and exclusion of anything religious from their analysis. Hence, when the Imam of the Grand Mosque in Makkah/Mecca told pilgrims in January 2005 to shun extremism, to protect non-Muslims in the Kingdom and not to attack them in the country or anywhere, and so on, it didn’t even register a single blip on the American media radar. Reuters picked up the story, it was relayed in a few countries world-wide (interestingly, one was South Africa), but that was it. For Muslims, particularly those living in Saudi Arabia, it was both major and radical in that he was given over three hours of prime-time TV during which he fully explicated the entire, moderate thesis regarding the moderate religion of Mohammed. For us living in the country and wholly reliant on Hadeel’s analysis for what was happening in the world of Saudi Arabia, it was very welcome news indeed. For it seemed to indicate not merely a formal rejection of that particular manifestation of Al Qaeda within the Kingdom, but also, more importantly, a different zeitgeist within the country and a clear break from certain extremist Wahhabi principles (this was around the time that a number of fire-breathing Wahhabi religious leaders were also shut down).

Previously, it had felt as if the population, at best, simply ignored the presence of non-Muslims in a country that could be famously intolerant of them, even before the discovery of commercially viable, extractable oil - Wilfred Thesiger was literally being hunted down to be killed in 1948 simply because, according to the dictates of a Wahhabi sect of that time, his mere presence within the country defiled it. After crossing the Empty Quarter for the second time accompanied by members of the Al Rashid tribe (who obviously did not share the other’s sentiments), and but for missing a shot at a buck and therefore pressing on, so close on his trail were his hunters that he missed being murdered only by this narrowest of margins.

|

| Shaybah, Empty Quarter, December 2007 |

Certainly, prior to the events of late 2003 and 2004, it was reported that “Many people like what bin Laden says. His actions are not what they are all about, but his slogans, yes. That is the question we have in Saudi Arabia: How do we deal with the people who like bin Laden's slogans, his ideas? It's hard.” (Khalil Khalil, a professor at Imam University in Riyadh, in Washington Post, 8 June 2004). Furthermore, a previous silence about the acts of terror “leads some Saudi intellectuals to conclude that the religious establishment, or at least its more militant elements, basically support Al Qaeda's goal of driving all foreigners out of the Arabian peninsula and establishing a Taliban-like caliphate” (NY Times, June 6, 2004).

But then, in 2005, when the religious establishment, in Mecca, nogal, at the beginning of particularly religious time in the calendar, comes out swinging against such sentiments, what is the response of the world press? Nothing. They simply ignored it. And certainly reading again through the articles for this email it is interesting to note that, on a related site http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Insurgency_in_Saudi_Arabia they talk about the requirement that Saudi crack down on the imams preaching anti-American rhetoric, but then do not note any instance of when such a crack-down does occur. Which is not to say that more couldn’t and can’t be done, but having recently converted to the sticker system to try and get my kids, at least, to be not as cluttery as we are (which means we are all, for all practical purposes, on the sticker system, but hey, it works!), you realise you really do need to reward and recognise all instances of required behaviour, not just ignore it, certainly not if you are wanting to encourage further instances of said behaviour.

Freud once said that a pre-condition for therapy was that the patient must be able to speak and the therapist to hear. Having proclaimed that the government and religious institutions should stop “using soft language” (NY Times, 6 June 2004) when talking about the problems of Al Qaeda in Saudi Arabia, the same press corps do not see fit to analyse the pronouncements of the self-same establishments when they take a hard line against such extremism, albeit out the mouths of the religious leaders. But at least, unlike all these analysts, we could count on Hadeel for both friendship and analysis.

So thanks largely to Hadeel and her husband Ammar, at least we were able to feel that ordinary Saudis were horrified by the violence and amazed by the audacity and hard-heartedness of that particular cell – which definitely turned the tide of sentiment against Al Qaeda in this country. Hadeel described how Saudi TV ran interviews with Paul Johnson’s Thai wife and his Saudi friends – he lived amongst Saudis, spoke fluent Arabic, loved living in Saudi, and was beheaded by the same cell that initiated a number of compounds bombings, then the Oasis incident and then a series of apparently random and isolated incidents of terror, including his death, while on the run. Hadeel described how everyone was so moved and upset, how they all sat there watching the interview, crying, how his Saudi friends talked about how much he had integrated into the country (making him a prime target in that he lived in an ordinary house in an ordinary suburb and not in a high-security compound). She was amazed by the entire coverage, how much time was given to it and so on. Once again, we are indebted to her knowledge and information.

|

| Hadeel and Ammar, Jordan, December 2005 |

The cell (whose leader had, of course, like all of the then top Al Qaeda operatives, been trained by the CIA in Afghanistan in the 1980s) had moved onto killing one-on-one after being stung by criticism after a 2003 bombing when most of the people killed were Arab and Muslim. Therefore they made the decision to undertake intimate killings. At the Oasis compound, they first ascertained whether someone was Christian or Muslim before murdering them; even debating among themselves whether to kill this one or that: “Yes, she’s Arab and says she’s Muslim but she’s not dressed in the proper attire, but at least she knows the Koran – should we kill her or not?” Reports from the survivors indicate that the veto of the older man veto counted, the younger one wanted to slit the throats of one and all. What made the entire situation particularly awful was the fact that people were trapped in their houses and hiding out, possibly wounded, but able to phone their friends – on Aramco, for instance, and give them a blow-by-blow account of what was going on as it was happening, so that during that entire time, we were all transfixed by horror and glued to our TV screens and really not sure at all what was really happening out there. Although trapped and entirely surrounded by security forces, the cell managed to escape – many here believe to this day that a deal was struck. Whatever the truth is, nonetheless, they escaped when they shouldn’t have. For some people, that was reason enough to leave – whether it was deliberate involvement or incompetence on the part of the security forces was of no matter to them\; either possibility was too awful to contemplate. When the cell was finally destroyed in a fire-fight at a garage in Riyadh, Ammar told us how SMSes delighting in the news were flying around and he got multiple versions of the same information, even as the show-down was happening, late at night. That told us more than anything else that your everyday, newly suburbanized Saudi Arabian did not actively support Al Qaeda. Which would imply that you would not be able to keep more than a few cells going, given the demands made upon ordinary people by such cells. And in the intervening years that seems to be borne out, though the situation of an apparently low-level of chronic terrorism continues.

But there we were in 2004, in a country famously secretive about everything from its security plans to its reserves of oil, living in our own, famous within the country, Aramco bubble. That we were surrounded by massive security was always known:

“Security has become the prime concern. At perhaps the most closely guarded compound, residents negotiate four checkpoints to get home. ‘This is essentially a family-oriented maximum-security prison with barbed wire and security gates and the whole works … People drive by enough fire power to stop an army and they ignore it.’ Entering any compound is like landing on another planet. Women bike around in shorts -- not to mention drive cars, which is otherwise illegal in Saudi Arabia -- while children gambol across lawns and streets (NY Times June 3 2004). It’s no rocket science to work out the compound in question is Saudi Aramco, Dhahran – in none of the others are women allowed to drive, which is a moot point, since none of the others are big enough for driving to be a reality anyway. For those who like images, the opening images of the trailer for The Kingdom are undoubtedly based on the old baseball park at King’s Road, Saudi Aramco, Dhahran. They’ve since built a new baseball park now and remodelled the previous one into a park suitable for entertaining the King (as happened in May this year) and celebrating ‘Id festivities. It’s particularly chilling to watch it, if you live here. The only thing they got wrong was the chairs – Recreation (a division looking after the 55 self-directed groups – i.e., all sports, cultural and other activities on Aramco) supplies bleachers and not canvas director’s chairs. Where individual chairs are requested, they troop out 28 year old steel framed chairs that I have been fighting, memo by memo, to change in the Women’s Group for the last four years (the Administrator told me last week the requisition order had finally been signed). But at least knowing they got the chairs so completely wrong helps me know it’s only a movie. The images of the housing block that are bombed are based on the Khobar bombing of the 1990s. For more historical imagery of Saudi Aramco housing compound, there was another video, but it seems to have been taken down.

Not long after the Oasis incident we had a talk at the Women’s Group by one of security’s head-honchos, formerly from MI5 (we also have ex-FBI and CIA staff, naturally) and he told us that he wished he had the resources Aramco has to protect the Queen of England when that was his job. A lot of his audience was singularly impressed by this, but I wasn’t sure if I really wanted to know that I was better guarded than the Queen of England, since it started to imply that I should begin to ask other questions, such as - but why do I need such a high level of protection? And what are the precise risks that are out there anyway? Which answers would, obviously, not be provided to me for reasons of - safety and security. Within Aramco we were fairly assured of our safety; oil countries on relatively cordial terms with international governments tend to be looked after, rightly or wrongly, and this was even before oil started its current upward trajectory (at the time it spiked to $ 42.00, a previously unknown high). What we were unsure of was how safe we’d be outside Aramco, although I did once work out that, in 2004, something like 120 times more people died in car accidents than were killed by Al Qaeda forces in Saudi. A cheering thought. Certainly it provides a second extremely good reason never to venture outside of Aramco’s security gates. Which is not as far-fetched as it seems, there are some single ladies who only leave camp to go to and from the airport. Literally.

|

| Manicured lawns of Aramco facilities |

When the articles did get around to describing life in the compounds, they’d talk about a “gilded cage with bearded guards” (Al-Ahram, 3-9 June 2004), and seemed to concentrate on the presence of manicured lawns with sprinklers, which seems to be a kind of shorthand for conjuring up a life of extreme privilege, for which imagery I think we may very well have to thank F. Scott Fitzgerald. “Expatriate life for the tens of thousands of Americans and other Westerners working here has long been about comfort. Sheltered from the harsher tenets of Wahhabi Islam by the high walls and hissing lawn sprinklers of their compounds-cum-country club, residents can usually pay off huge debts, put their children through college or build a retirement nest egg by settling here for a bit” (NY Time, 3 June 2004). Certainly lawns in Saudi Arabia are both sufficiently unusual and unnatural that they do provoke a definite response; on the other hand, they are not quite as ubiquitous as some of the writers depict and are often maintained, not by high-level sophisticated lawn sprinklers, but by a phalanx of lowly paid, under-fed, and sickly workers invariably of Bangladeshi origin. Of course you get lives of cocooned privilege here, as everywhere, and particularly in Saudi Aramco, Dhahran (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saudi_Aramco_Residential_Camp_in_Dhahran) but what I am driving at is the fact that when a few intrepid souls did venture into compounds within the area to describe what life is like in Saudi Arabia, they focused on the upper end (and, after all, the Oasis compound where the incident occurred does very definitely occupy that end, having its own skating rink and so on), but then were somewhat disparaging about who and what they found there, damning with faint praise, as it were. As someone who has lived for an extended period of time in the lower end of the highly skilled expatriate work force, I can testify that not all lives are like that. Some of the writings are infused with a definite, underlying sense of Schadenfreude or “largely unanticipated delight in the suffering of another which is cognized as trivial and/or appropriate” (Theodor Adorno). Social scientists seem to feel Schadenfreude is triggered by envy or resentment, the resentment happening when good fortune is seen to be undeserved.

Hence the terms of the argument in terms of staying or going were almost exclusively framed by the press in monetary terms: “But in the past year, with terrorist attacks across the country claiming the lives of more than 75 people, the equation has begun to shift. Many expatriates are weighing the benefits of high salaries, good schools, great travel and exposure to the exotic against Al-Qaeda-inspired terrorists bent on killing Westerners” (NY Times, 3 June 2004). Which pretty much made me feel like nothing but a carpetbagger (or outsider who seeks power or success in a new locality presumptuously). But then again, I guess, if you are going to do something there’s no point in not doing it properly. Which is not to deny that many of us do lead enviably privileged lives here (many do not), and that we are, indeed, surrounded by many carpetbaggers, particularly those leaving the country (since collecting carpets is a very real possibility here and at that level, Fem and I have become carpetbaggers of note). But the implication in many of the articles that either current fortune is somehow undeserved or subsequent misfortune is somehow deserved made the whole situation a particularly toxic one to live through and decode. Perhaps for the reporters it was not the fact that they found wealthy individuals in Saudi, since you find them everywhere, but more the fact that people could be doing otherwise common-or-garden work and yet be paid large, tax-free sums money for undertaking it is what triggered their feeling of Schadenfreude. Growing up with a sense of guilt a la apartheid South Africa perhaps made me peculiarly sensitive to such insinuations.

I found it difficult to write about. I still do. But the desert remains within me, forever

|

| Shaybah Sunset |

Comments

Post a Comment