Father's Day: The True Nature of Courage

|

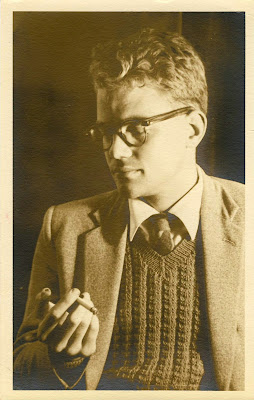

| My father as a young man |

My father should have died when I was two, but he didn’t. He died when I was thirty-five instead. Thirty-three years of living a life that cancer should have compromised to such an extent that for many people it may not have been worth living. And yet, every day that he woke up, he woke to work and loved his work, and though he seldom sang, his whole body sang with joy; he laughed, he joked around, he was a happy man. The more crippled his body became, the more his soul shone through.

In fact, it was only when I sat there next to his hospital bed when his final bout with cancer finally took his life away, that I first saw the X-rays of his body, taken years before, and which finally mapped out to me how singularly twisted and sinister a disease had taken hold of him.

Sketched in white against the dark, I saw the bird bones of my father’s frame, twisted out of almost all recognition, deformed, alternatively thinned and knobbly, devastated by the cancer that had metastasized to his bones, many, many years previously.

It looked like a still from a horror movie. Except that it wasn’t.

In 1968, my father was diagnosed with Hodgkinson’s disease, a form of lymph cancer. At that time, cancer was a death sentence. There had only been one report of cancer going into remission some 18 months previously; that cancer happened to be Hodgkinson’s. The medical establishment sent my father home to die. He refused to die. Instead, he accepted all the guinea-pig treatment they could throw at him. The radiation alone was enough to kill a bull elephant in its prime, and then the years of chemotherapy, uncalibrated and indelicate, unlike today’s more measured doses, affected his heart among other things.

The first series of radiation treatments I am too young to remember, the second, harsh regime of chemotherapy some three years later I do remember, mostly because of my keen disappointment that the proposed trip to Cape Town, by train! which I had written about and sketched for my Grade 1 class, was cancelled and my mother bought a tumble-dryer with the refund instead. Interestingly enough, instead of holding a grudge against the cancer, to this day I still hold a strange, unyielding and peculiar grudge against Cape Town, which certainly cannot be blamed at all for my father’s cancer, but many times when I hear the word “Cape Town” out of context, a strange sensation of disappointment immediately accompanies it. How peculiar is the human mind? But if that is its way of shielding the young brain from the contemplation of death, I guess I’ll comfortably live with it.

After the second remission, all was seemingly well for approximately ten years, at which stage we had just arrived in America for a few months (my father having accepted an IBM fellowship there to work on a project so the family could have some international travel under their belts) and they then diagnosed what they felt at the time was a second, full-blown re-occurrence of the cancer (they did not have the same understandings then of it as a chronic condition, particularly those cancers, like breast cancer, which have to do with the lymph system). And then we faced another few years of treatment after treatment after treatment.

My father wasn’t perfect, but there were many things I learnt from him in his battles which cancer which have forever informed my life.

My father focused on what he could do, and let go of the rest. He never second-guessed his doctors, or expected perfection of them. No matter how harsh the treatment regime, he bore it stoically and cheerfully. I remember, in Palo Alto and then Dallas, he’d time his regime so he could always put in a full day at the office, before he came home and hurl his guts out, before getting up early the next morning and, if need be, doing it all over again. He always said that his job was his to do, the medical professionals had their job to do and frankly, they were the ones making the decisions so he’d leave them to do their job best.

I remember how proud he was when the team of which he was part said that he had produced twice as much as they had expected out of him for this particular project, not taking into consideration how very sick he was at the time. He always said that work was his salvation, and he figured he'd delegate worrying about his cancer to the doctors who were trained professionals, while he'd worry about his corner, which he could manage all by himself, thank you. He was always so deeply grateful for modern medicine and its myriad miracles. I think we've become blase about our healers and don't appreciate them enough either. There is something quite delightful about leaving the medical establishment to worry about their work; I found it saved me when my two-year old daughter was bitten in the face by a dog and had to have emergency surgery late at night, I could recite to myself, like a mantra: she's with the professionals, they're doing their job. Go home, sleep, look after the other kids (dad stayed with her overnight since he didn't know the boys' schedules and we do have three children after all).

I remember how proud he was when the team of which he was part said that he had produced twice as much as they had expected out of him for this particular project, not taking into consideration how very sick he was at the time. He always said that work was his salvation, and he figured he'd delegate worrying about his cancer to the doctors who were trained professionals, while he'd worry about his corner, which he could manage all by himself, thank you. He was always so deeply grateful for modern medicine and its myriad miracles. I think we've become blase about our healers and don't appreciate them enough either. There is something quite delightful about leaving the medical establishment to worry about their work; I found it saved me when my two-year old daughter was bitten in the face by a dog and had to have emergency surgery late at night, I could recite to myself, like a mantra: she's with the professionals, they're doing their job. Go home, sleep, look after the other kids (dad stayed with her overnight since he didn't know the boys' schedules and we do have three children after all).

Even when, once, the needle jumped out of his skin because of a blockage further up in the vein, and a few drops of, amongst other ingredients, mustard gas in solution dripped onto his arm, and for 18 months he carried a deep crater in his arm that was unbearably painful and took forever to heal, he’d shrug his shoulders and say, Oh well, we all make mistakes. He never held a grudge, against humans or the cancer itself. What was, was.

I don’t know if my father lived so long because he was an optimist; the statistics say that optimists die just as frequently as pessimists when it comes to the cancer survival rate. I believe that he lived because he believed. He believed he’d live, and so he did for far, far longer than he ever should have; we always knew, all the years we had him in our family that we were living on borrowed time.

To my deep shame, I remember once during these High School years, which were significantly blighted by these long years of fighting cancer, feeling just so repelled by my father. He was so ill and his body exuded the most peculiar smell, almost metallic. Not off-putting per se, just peculiar. He was a sick man, for most in our community, a dying man, and my mother would walk into the supermarket and find people quickly walking to the other aisle so as not to speak to her. People often think they should offer you words in such an instance. Words of advice. What do they know, though – what do any of us know? All we wanted was someone to say, “Hey, how are you doing?” And Listen. We don’t listen enough, that’s what I found. You don’t have to say anything. Anything at all. But being there – Ah, now that’s a treasure.

Anyhow, I remember well a day when my father, sitting next to the fireplace at Lynn Avis, my grandparent’s small farm near Ixopo, asked my cousins about their recent trip up Langalibalele Pass, which is a severe hike in the Drakensberg mountain range, up which Chief Langalibalele had fled with his tribe during colonial times. My father’s blue eyes shone with joy as my cousins, young and strong and healthy, told of going up the pass with their father, and my father asked them now this question and then that, drinking in their journeys with his eyes. What I did not realise then was how often he, as a young man, had journeyed into those very same mountains, so it was as much a trip of remembrance for him as it was about hearing it for the very first time.

I thought then – oh, wouldn’t it be lovely to have a father that was young, hale and hearty instead of this crippled train-wreck of a man. Such is the insensitivity of youth.

What I realised over the years, and treasure deeply now, is that that day I was first confronted with the true nature of courage.

Courage is learning to face life square, with all it brings, and making the best of it, every single day. It’s learning to take life as it comes and still being happy with your portion, however big or small. My father’s gift to me was showing me that even if you can’t climb mountains any more, that doesn’t mean you can’t be infected with the joy of those who still can climb mountains.

When I saw the X-rays of his bird bones and realised that this was what he’d been carrying around all those many years, never complaining, always cheerful, I thought back to that day by the fire and realised then that sometimes the mountains you don’t see someone climb are the most important ones of them all.

Comments

Post a Comment