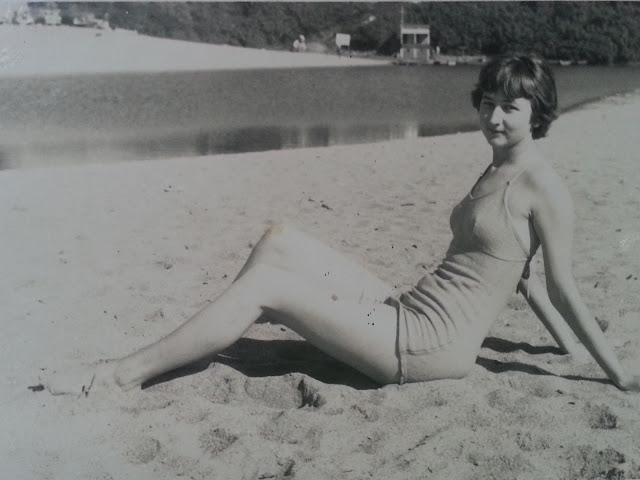

My mum, a eulogy

|

| Mum as a young woman |

Considerate to the last, mum died on a Saturday morning when the sun was shining, the birds were singing, and I could be with her.

Her years of pain and suffering, of fighting cancer so she could spend more time with her precious grandchildren, Faran, Jessica, Conall, Bethany and Emma are finally over. It is now that we must give thanks for all she was to us, and remember the essence of who she was.

Before she died, mum asked me to take down these words for her grandchildren. It’s in the form of a short and simple list found on the last page of the pamphlet.

She called them, “Grandma's Life Lessons”:

1. Be Honest.

2. Be Kind.

3. Have Good Manners.

4. Wash Your Hands.

She said these are good enough words to live by.

Mum certainly lived her life according to these wise precepts and today’s reading focuses on loyalty, kindness and wisdom, all of which were exemplified in human form by mum.

Mum was unfailingly kind; going to the shops with her was a bit like being in the entourage of a stately queen, one who has never lost what they call the common touch. Not only was she always uncommonly elegant, in a very French and understated manner, but she simply had to stop and spend time with everyone she knew en route. The most vociferous car-guard would drop their voice in volume and tone as mum would stop for the latest update on their family; she knew the names of everyone, from cashiers to store managers, and would stop for long, quiet conversations wherever she went. God forbid it if you were in a hurry and she met someone she did not know and who had a story to tell – in her quiet, gentle manner she would elicit the story out of them, regardless of the ice-cream melting in the grocery bags all the while.

When I asked Faran what he wanted to say about his grandmother today, he said, “You know, just that she is always so kind and she always does her very best to help us.”

Mum’s loyalty was borne out of her kindness and was of the quiet, stoic kind – never one to make a song-and-dance about anything, she would simply gird her loins and do whatever needed to be done. There is the brief memoir she wrote once of the time when she was staying with her grandfather and his third wife, Sue.

It is telling in that she undertook this simply in order to be close to her much younger sister Sylvia and her niece Lynne, who were then boarding with Sue in Ixopo. It was not a happy time – the siren song that was her father’s farm, Lynn Avis, had meant mum never finished her schooling and left with only a Standard 8, which lack of formal education remained a wound, gave up her dream of going overseas - since she lent the money Uncle Frank had bequeathed her to her father to help with Lynn Avis - and now, just as she could have been living anywhere, there she was, working in Ixopo, helping her parents eke out a living and then even boarding with Rex and Sue to remain close to her baby sister and Lynne, both of whom remember her as a great comfort and shining light during this time.

Aunty Sue had a good heart underneath all that gruffness but she didn’t understand children at all, and mum always had a deep and abiding sympathy for children; an innate insight into them and their concerns, as she had with all people, both little and big. This is mum’s hilarious account of a miserable evening:

“... in the evening when Sue returned from School, they would decide that the “sun was over the yard-arm”, that the “hour of sacrifice was nigh” and it was clearly “time to roll out the bottles.

"In the meantime, the food slowly lost its really fresh taste in the Aga warming oven, and we at the second or third row of the small fire slowly froze. Eventually we sat down to food that had that strange over-warmed flavour, over-dried food, served with extremely greasy gravy.”

Lynne Gordon wrote to me after mum’s death, saying: “I will always remember her as a serene gentle soul always there so strong and comforting in my early years of school. I don't know if I would have survived without her support ... Your Mum took a big part in my growing up years and I am always grateful for that, and I loved her dearly ... she lived a good life and touch(ed) so many with her kindness and gentleness, a very special person who I shall always remember and hold close to my heart” (Lynne Gordon).

Addressing my mum directly, Sylvia said to my mum, her sister, at a celebration we had of her life some eighteen months ago, when she was still just well enough to travel:

“Les, you always were and are still, my mentor, my teacher and my guide:

· Always there for me – letting me be who I am without criticism.

· You taught me so much and looked after me during the sometimes dark days of my childhood.

· You gave me books and I learned to appreciate Poetry and Literature because of your knowledge and encouragement.

· A long time ago – you gave me one of your poetry books, from which, one evening as we sat around the table in the kitchen at Lynn Avis, I read excerpts of poems. You finished them off and named the poets. Dad was impressed. “You are incredible!” he stated with great admiration. “Of course she is,” mum said as she peeled potatoes.

Great literature delights in all our human frailties as well as our grand endeavours that are larger than ourselves. Mum had a particular relish for the ridiculous, and I cannot recall how many times she’d phone me up with a funny quote or read out to me an extract that tickled her fancy. She delighted in dad’s quirky sense of humour, he who was the love of her life. She remembers once fighting with dad, as married couples do, and threatening dire consequences, to which my father replied, in an utterly matter-of-fact tone to her, “Oh no, you’ll never leave me”, waving her statement away with one hand, “You’re far too loyal for that - that’s one of the reasons I married you, I saw how loyal you were to your family”. Mum, laughing wryly afterwards, remarked that dad was absolutely right, of course, however she felt he need not have been quite so very complacent about it.

After dad died, mum was pitched head-first into a deep and prolonged grief, and her lifelong battle against depression, which was only diagnosed with her late in life, became again a major factor and deep shadow in her life; something that sucked vitality and energy and joy out of her. To those fortunate enough never to have navigated these dark waters, the sheer grit involved in simply enduring cannot be under-estimated, but mum always strove despite everything to be neat, to be clean, to be brave.

For mum, an inveterate lover of poetry, to me the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem best encapsulates the keen sense of overwhelming despair severe depression brings upon you: The poem reads -

No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief,

More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.

Comforter, where, where is your comforting?

Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?

My cries heave, herds-long; huddle in a main, a chief

Woe, wórld-sorrow; on an áge-old anvil wince and sing —

Then lull, then leave off. Fury had shrieked 'No ling-

ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief."'

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne'er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep. Here! creep,

Wretch, under a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death does end and each day dies with sleep.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Mum fought her depression the old-fashioned way, with grit and dignity, and immersing herself in the everyday life of this world, in routine, in cleanliness, in always being elegant and neat. Even after my dad collapsed on the verandah, and they were taking him to hospital, mum was seen to pop back into the house and emerge with a slash of lipstick on and a scarf around her neck, looking as serene as a swan, despite much paddling underneath.

|

| Mum, who always looked as serene and elegant as a swan |

When we later on remarked on the fact she was never without her lipstick, mum said she felt naked without it, then, looking to the right, with a wry smile on her face, she remarked: “Come to think of it, if the house was burning and I had to chose between my knickers and lipstick, it would be a close-run call”.

However, when this was not enough, when the sheer, no man-fathomed cliffs of fall proved almost too much for her, we are immensely thankful for her wonderful care by Dr Stewart Lund, which gave us back our mum with all her quirky humour and wisdom.

For mum was immensely wise, in large part because she not only took great solace in books, but enjoyment too.

Like C.S. Lewis, mum “had always the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks into a field has of finding a new blade of grass.” However, she does recall a stay once in a hotel, where there was nothing to read but the telephone directory and she and dad hands both touched it at precisely the same time.

Mum wrote to me of her introduction to the world of literature, through a Mrs Dorning when they were staying at Krom Drift in East Griqualand and which she remembers as “a world made for children” and a “magic year”. She writes:

“We had dogs, cats, a huge garden and an orchard. There were acres of farmland to wander at will, and a river ran through it, very crookedly, which why it was called 'krom'. Willows grew along the banks of the river, and nearby there was a huge shallow vlei, which attracted wonderful birds. I remember especially the Crowned Cranes which have always been my favourites.

"Kelson sometimes went to the banks of the river where the umfaans taught him to make clay oxen and horses - a skill he still has to this day. We sat in the branches of the willows overhanging the river, and smelled the river-smell, which Rupert Brookes has described so exactly:

"To smell the thrilling-sweet and rotten

Unforgettable, unforgotten

River smell ...”

"Mrs Dorning of Fearnley farm had arrived in South Africa as a Governess. She was tall and gawky, with a long nose, bony hands, long feet and an infectious laugh, and very endearing. We loved her. She had married a practically illiterate farmer, and their sons went to Michaelhouse. Old Mr Dorning told us that he was sent when he was about ten to look after the sheep on their Berg farm - about 20 kms away. He went to sleep one afternoon, and woke to find vultures sitting round him.

"Anyhow, Mrs. Dorning introduced us to The Wind in the Willows and I have a picture in my head of us bathed and in our warm pyjamas, sitting in front of the fire, with the dogs around us, my grandmother playing Just a Song at Twilight on the piano. Outside the bare poplars are etched against the pale apricot and lemon sky, and we were warm and happy, with our favourite people, having our favourite story read to us.” At which mum adds, in her inimitable way, “(You see why bathing is so important to me?)”

|

| My mum reading to my freshly bathed brothers Nils and Piers, in the pyjamas Ingrid sent from Japan |

Last week, I found this poem in amongst a book of papers my mum had put together. I wrote it many years ago, and sent it to her, along with a few others, in a letter typed on the IBM Selectric typewriter my dad bought for me.

Mum kept all my letters, and recently took to sticking them, together with other sundry papers that were important to her, into a book. Considerate as always, she needed to ensure all her affairs were in order before the end.

Reading this poem again, which was written for my mother - and women like her, it seems almost prescient.

I did not know then she would have to endure harrowing years of physical pain and suffering, which she bore with such dignity, during her fight against cancer. Despite all her pain, the last Monday before she died, barely able to talk, she had insisted my brother phone me so that she could tell me, again, that the day I was born was one of the very happiest of her life.

In the poem, the "purple hearts" refers of course to the award given to those wounded or killed in service by the US; while "Little women" refers to the series of books by Louisa May Alcott.

It's meant as an ode to domestic women everywhere, who selflessly serve - and often without recognition.

Purple Hearts: Poem for my mother

Purple hearts on her socks -

She is brave beyond

The sea, the sky, the tree;

Have mercy.

Each night she locks

Inside

Flowers, the scent of poetry,

Samuel’s bigotry.

Selfless, her self

Fills with others’

Heads, hearts, knees.

Float a darkened sea –

Little women

Should be so put upon,

Cut without bleeding -

Care without needing.

Kathryn Kure

Dear mum, you were so much to all of us; and your love of poetry, your wry humour, your kindness and loyalty have certainly given all of us wonderful life lessons which enrich us every day. I will end with a short verse you wrote into the back of the poetry book you have to Sylvia, an excerpt from one of your favourite poets, Rudyard Kipling, which reads:

“A certain sacred mountain where the scented cedars climb

And – the feet of my Beloved hurrying back through Time”

Rudyard Kipling

Comments

Post a Comment