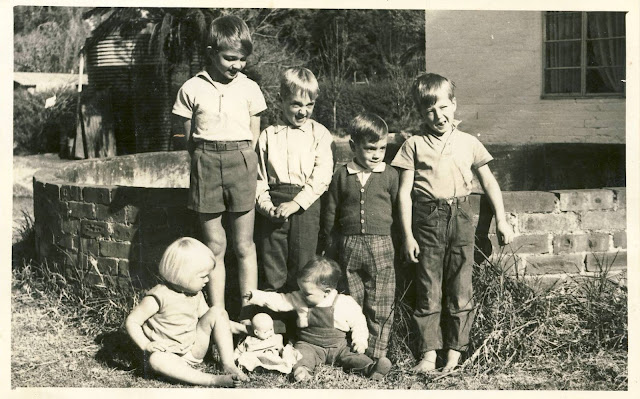

Look At All the Fire Folk! Part 1

LOOK at the stars! look, look up at the skies!

O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air!

The Starlight Night, Gerard Manley Hopkins

It was a still day. The veld so dry, there was a haze in the air, and motes from the fire hung there for long moments at a time before tumbling slowly to earth. Thin smoke rose high into the sky, feathering out towards the top, where the wind finally began. Despite grandpa’s warning that should the wind rise and change – in which case, dire consequences were sure to result … it never did.

Instead, the boys delighted in becoming totally smoke-blackened, whumping great wet sisal sacks onto the grass fire begun in order to reburn the fire-break. There was no real danger of the fire getting out of control in the still air, and the autumn grass, though tinder-dry, was shorn short by the cattle.

Nonetheless, the thread of terror engendered by a fire ran through them all, and the boys’ delight in the wildness of a fire was not tempered, but rather, heightened by the dangers implicit therein.

The entire morning they whooped and yelled, now beating back a series of flames, now bashing into extinction a smouldering ember which had once been a grass clump. Farmers and labourers from all around worked together, subduing the fire such that it burned the landscape into the shape required to keep their farms and lands safe.

The fire was of a different mind altogether; impulsive, gregarious, ever-expansive, it desired to consume all – lands, farms and people alike – in fiery ecstasy. The leaping flames mesmerised both boys and adults, murmuring of confinement, and persuading them to let it free, free to leap the barriers imposed by the fire-breaks, free to devastate the nearby valleys and hills and beyond.

But, knowing how formidable the fire’s powers were, they were not seduced. Indeed, this year’s fire-break was to be extra large, since a fire had leapt across last year’s fire-break, though fortunately enough at a time when there was no wind. Thankfully also, grandpa had eyes like a hawk and ears like a deer and had detected the fire early enough to enlist help to drive it back – as it was, it was too close a call.

In the still air, even the sun’s weak rays were felt through the thin material of their shirts, and, soon enough, all the boys and most of the labourers had stripped down to their waists. Many a farmer would have liked to join them, but dignity and a beer belly dissuaded them otherwise. What with the fire in front, the sun behind, and the extensive fire-beating undertaken, it was hot and sweaty work. The intensity of this small fire was almost unbearable; but nothing at all in comparison to tackling a roaring veld fire in the middle of a summer heat wave.

The burning of the fire-break was completed by mid-day, and the neighbouring farmers gathered back at the farm to drink the obligatory cup of tea wolfed down with sponge cake still warm from the oven, its two halves stuck together with home-made raspberry jam and with icing sugar lightly dusted on top serving as decorative effect. It was almost ludicrous to see such a dainty repast held in the large, hard-working, dirt- and soot-encrusted hands of the farmers, particularly since some of them took, absent-mindedly, to shaking the icing sugar off the top as if it were dust.

The farmers were mostly silent when eating, apart from a few nods and perfunctory greetings to grandma when she arrived with the tea and cake, as they stood there, still dripping from their exertions. They were most conscious of wiping the sweat off their brows and not one would even come into the kitchen, instead they stood milling around outside the kitchen-door, like cattle before a gate, uncomfortable and silent. As soon as they could possibly manage it from the point of view of politeness, they took off back to their trucks, but that’s when the talking began!

For a farmer to load himself and the labourers from his farm into his truck took a matter of minutes – but getting away thereafter always seemed to take forever. Not one of them ever seemed to be in much of a hurry when seated in a truck, despite their protestations to the contrary when standing around in the yard. Once ensconced in his own vehicle, however, why, each farmer was king of his own domain again, and as gossipy as any newspaper man.

Mr Carter-Brown, in fact, stayed for a further three-quarters of an hour after all the others had left, chatting to grandpa who stood talking to him at the front rolled-down window, with Mr Carter-Brown’s elbow sticking out right besides grandpa’s ear. He must have said goodbye at least four times, with grandpa twice even walking backwards away from the truck preparatory to its departure until yet another incident or story in the farming community update process was recalled which brought him back steadily towards the window.

Grandma always stood a ways away, far more able just to say goodbye and be done with it, since she always had work beckoning her at the house, but she was far too polite to walk away until all her guests had departed. But finally even Mr Carter-Brown’s truck’s wheels began crunching on the gravel driveway encircling the farm-house as grandpa and grandma waved him goodbye.

|

| Mum, grandpa, grandma and the dogs i nthe gravel drive-way |

After Mr Carter-Brown had left, the two of them stood there for a moment or two, completely silent, then grandpa said to grandma, “Well, that’s that, then!” and grandma looked at him and gave her customary brusque nod, with a slow smile on her face. They walked back together towards the farm-house, their steps in synch, saying nothing. At the door to the kitchen, grandma went in to prepare a hearty repast while grandpa took a deck chair out to under the pine trees and lay there with his head underneath his large brown hat, resting and thinking over all the stories of the morning. The process of mulling the stories over, preparatory to story-telling time that night, invariably had a soporific effect on him, so that he would have to be woken up for lunch.

|

| Grandpa, mulling things over, preparing stories |

Not satisfied with the morning’s exertions and activities, the boys had decided that they’d take a neighbouring farmer up on his kind offer and go wandering towards the hills, searching for the stream he’d told them ran on his farm, in anticipation of a quick cool dip.

They took the ever-eager dogs with them, dogs which, having been cooped up in the kitchen all morning because of the dangers involved in fire-break burning for over-enthusiastic dogs, were therefore more than usually ecstatic to be out and about.

The water they found was indeed crystal clear and cold from the ‘berg streams that run around and through the area of Ixopo, which is high enough to be cool and misty but the days are long and lovely and hot enough that you can bask on the rocks beside the pools, like fat, happy lizards.

That evening, they came home with the tired dogs, the long shadow of the large hill, Mabedhlana, abreast on the earth beneath their feet, with the fire-blackened grass crunching in a very satisfactory sort of a way underfoot - in their case, under bare foot. They’d even been bare-foot fire-beaters; such was the thickness of their soles, they functioned as shoes.

|

| "There is a lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hills are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond any singing of it." (Alan Paton) |

According to grandpa, who waxed lyrical after his mid-day ruminations on this very matter, it was a miracle that not one boy had plunged his foot into a hole in which fire still lurked, deep underground, since the slow burn of a tree stump can turn an entire root system into a hollow trap in which the foolhardy or unwary can be caught, with grandchildren clearly ranking foremost in both categories in grandpa’s book.

The fact that the fire had been lit under very controlled conditions, and had hardly been burning for hours did not factor into grandpa’s, but did enter their parents’ equations. Grandpa was full of cautions and warnings, doom-mongering and nay-saying, despite having lived such an exciting and adventurous life.

The seemingly contradictoriness of his own exciting life and his anxiety for others was hard to reconcile. Maybe his care for others was precipitated by his beloved mother’s death when he was only seven, and already the eldest of five boys for whom he always felt, and was also made to feel, responsible. Maybe also, trained as he was in First Aid, and having worked in the mines and endured six years in the Navy, without home leave once during the Second World War, he knew just all too well how easily an accident can occur, hence his natural anxiety had been fed by an awareness of misadventures. Not that his mutterings ever concerned any of the grandchildren much. They had the buffer of their parent’s experience between them and grandpa, not to mention the fact that, despite grandpa’s portents of gloom, their parents had all grown up. Indeed, without that fact, none of them would have even been here.

That night, in celebratory mode since so many of the family were assembled together, and in a nod towards the cold of the night air, the fire in the belly of the coal-burning Wellstood stove served up a great soft sponge cake, drizzled all over with warmed-up honey, and brought, piping hot, to the table, a simple but magnificent dessert. This followed on from, and provided a counterpoint to, the main meal which consisted of soup and fresh brown bread.

Grandma only ever made one kind of soup, really, a proper farm-style, rustic soup, soup that almost needed to be eaten with a fork. The basic approach was always the same, though some slight variations would be introduced by whatever fresh ingredients were available.

First, a shin, or maybe two, would be sealed at the bottom of a pot and pan-fried in a little bit of butter. Next, a kettle-full of boiling water – boiling so as not to bleed the juices from the meat – would be added to the pot, together with some mixed herbs and other green spices and a cup of four-in-one soup mix, accompanied by an extra handful or two of barley if my mum was around, since she was so particularly fond of barley. The mixture would be brought to the boil, while carrots, onions, parsnips, and potatoes - whatever root vegetables were available - were cut in chunks and added to the pot in a definite order – potatoes toward the end so they didn’t end up turning the soup into a stew.

Brought down to a rapid simmer, such that it boiled away rapidly but quietly, the soup would be left so that all the ingredients could start “talking to each other”, as grandpa, chuckling, always put it. For him, cooking was mostly alchemy; all grandma ever needed to complete the picture would be a long, pointy silver hat but she never had time or inclination for such silliness. For she could be a tough, dour Scot on occasion, and for her food was a serious business which she treated with due scientific respect, working within her limitations of stove and ingredients but always carefully observing both process and results.

As the soup boiled away, ingredients such as tinned white beans, or fresh green beans, or other fresh and tender vegetables would be added to the soup, at differing times, to ensure they never became overcooked and bitter. Finally, the tomatoes would be cut in half-an-hour before serving, and five minutes before-hand, copious quantities of fresh chives and parsley straight from the vegetabel garden would be added to the soup which was then served with thick slices of fresh brown bread.

After this filling and wholesome supper, replete with good food, the boys sprawled around the fire-place, faces upended in its glow, long legs all in a jumble behind. Already, they had their mattresses and sleeping bags out, since the lounge was where they slept at night and there was no point not falling asleep after, or even during, story-telling time. Besides which, they were tired from the day’s adventures.

|

| Grandma, whose hands were almost always busy with work |

Grandma, bustling around, making food and love last long, was the quiet backdrop against which each story unfolded, as integral to the evening as the fire in the furnace was to their enjoyment of winter nights. Tonight she thankfully didn’t have too much washing up to do; such was the beauty of tonight’s meal, so she and the rest of the womenfolk of the household rapidly set to cleaning up. One plastic bowl for the dirty dishes, one plastic bowl full of boiling water to rinse off the dishes, a place on the table where the dishes could be left to drip dry, on top of a clean wash-cloth. Then they were done, though grandma always found something to busy herself with for a few minutes before she was ready to put all domestic concerns aside and simply relax. But maybe it was also her way of gathering breath, in her own company, gaining for herself some quiet time alone, that she needed. Whatever it was, you never could dissuade her away from pottering around silently in the kitchen for a little while before joining the rest of the family.

But story-time never really began until grandma was there and had trimmed the paraffin lamp on the mantelpiece of the red brick fireplace. Then it was that grandpa would assume the story-telling position, right leg over the arm of the green chair, with possibly a dog ensconced on his lap. When they were younger, the entire tribe of kids would squabble for access rights, bitterly contesting that small space on the hearth beside him. Now, they were content merely to litter themselves about the floor, all elbows and knees and hard, bony bits.

A story they always clamoured for was that of how grandpa, when young, had made himself a little house amongst blocks of hay stacked up for winter cattle feed. He had smuggled into this hideout a greatcoat, a packet of biscuits a candle and some matches. He was intent on eating his stolen biscuits in the light of the candle while clad in his dad’s ‘borrowed’ greatcoat. As the eldest of many boys born one after another, privacy was something that was in short supply for him, and he grew very fond of his wee house amongst the hay, making the trip to and from the little room on numerous occasions.

|

| Grandpa next to the fire-place, the place of prime story-telling |

One day somehow, he never knew precisely how though he had his theories – the candle had either tipped over or a piece of burning wax had fallen onto the hay bales below – a fire was started. He tried to put it out, then realising it was useless, struggled out of the passage between the hay blocks, smoke in his face, in a great panic, leaving his father’s greatcoat behind. When already in the passage he realised this, but at least he knew he could not go back. Standing outside, looking at the conflagration he had started and knowing it would burn down that entire block of winter feed, he decided to flee the consequences. Running away from home and trouble, he fled into the wilderness that was all around the farm. At last, tired and terrified, he stopped at a stream only to find a leopard drinking from a rock in front of him. This decided him, so he turned to home, and the arms of his little mother, who, crying at the evidence of the burnt buttons, simply enfolded him into her arms, such was the sole punishment meted out to him.

He elaborated the story, each child anticipating every new crisis, each climax in the story, being as fond of the direness of the deed as the happy ending. Clustering around the dull, painted red brick of the fireplace, they remained hungry and clamorous for stories, stories, and yet more stories!

For Part 2, click here

For Part 2, click here

Comments

Post a Comment